NFTs are nothing new

# April 5, 2021

NFT’s have exploded into mainstream conversation over the last few weeks. Like with everything in crypto, you have strong bulls and equally strong bears on the investment thesis. It’s an ephemeral good, which defies many of our existing assumptions about object ownership. It’s a novel investment class that’s only made possible by the blockchain and distributed ledgers.

But really — are the principles behind NFTs anything new? And what can collector culture tell us about the investment opportunities with these new tokens? Here I sketch out a framework to assess NFTs and some market opportunities to create value in the ecosystem around them.

A Brief Recap: What’s an NFT?

If you have a basic knowledge of how cryptocurrencies are traded, you’ll be able to easily understand how an NFT is minted and exchanged. By way of recap: let’s say that you’re looking to buy 1 Bitcoin for 10 Dollars. There is a token (Bitcoin), a seller (or source wallet), and a buyer (or destination wallet). A transaction is conducted when a seller agrees to transfer that single Bitcoin to the buyer for 10 Dollars. They exchange the USD and the seller transfers the Bitcoin to the buyer, which is added to the growing ledger of other transactions within the blockchain. You’re then able to say definitively how much Bitcoin the seller and buyer have after this transaction.

If anyone is willing to sell me one Bitcoin for $10, please do let me know.

An NFT is effectively its own token like Bitcoin, Ethereum, or Monero. Most commonly, it’s an Ethereum contract, but this is a small technical detail. NFTs transfer like a token where you can send and receive them to your wallet address. Except unlike cryptocurrencies, by definition there is only one NFT. You can audit the contract line-by-line and ensure that only one can ever be created. This provides a guarantee of scarcity.

The acronym NFT stands for a “nonfungible token,” which reflects this definition. It means it can’t be broken down into other parts. You buy and sell the whole thing. This is different from traditional cryptocurrencies, where you can split them: like a twenty into fives or like a dollar into cents. Here, the smallest common denominator is the whole good. You can prove that you’re the owner of that one copy by ensuring that it is assigned to your correct wallet address.

This provable ownership solves a common problem in digital goods, namely that they’re infinitely copyable. You can losslessly copy a file and the original will be identical to the clone. Unlike a Picasso, where there was a clear original and then many forgeries, no such inherent distinction exists online. NFTs attempt to address this problem by allowing creators to mint only one token and cryptographically prove there can only be one holder. All other clones are easily detected as forgeries.

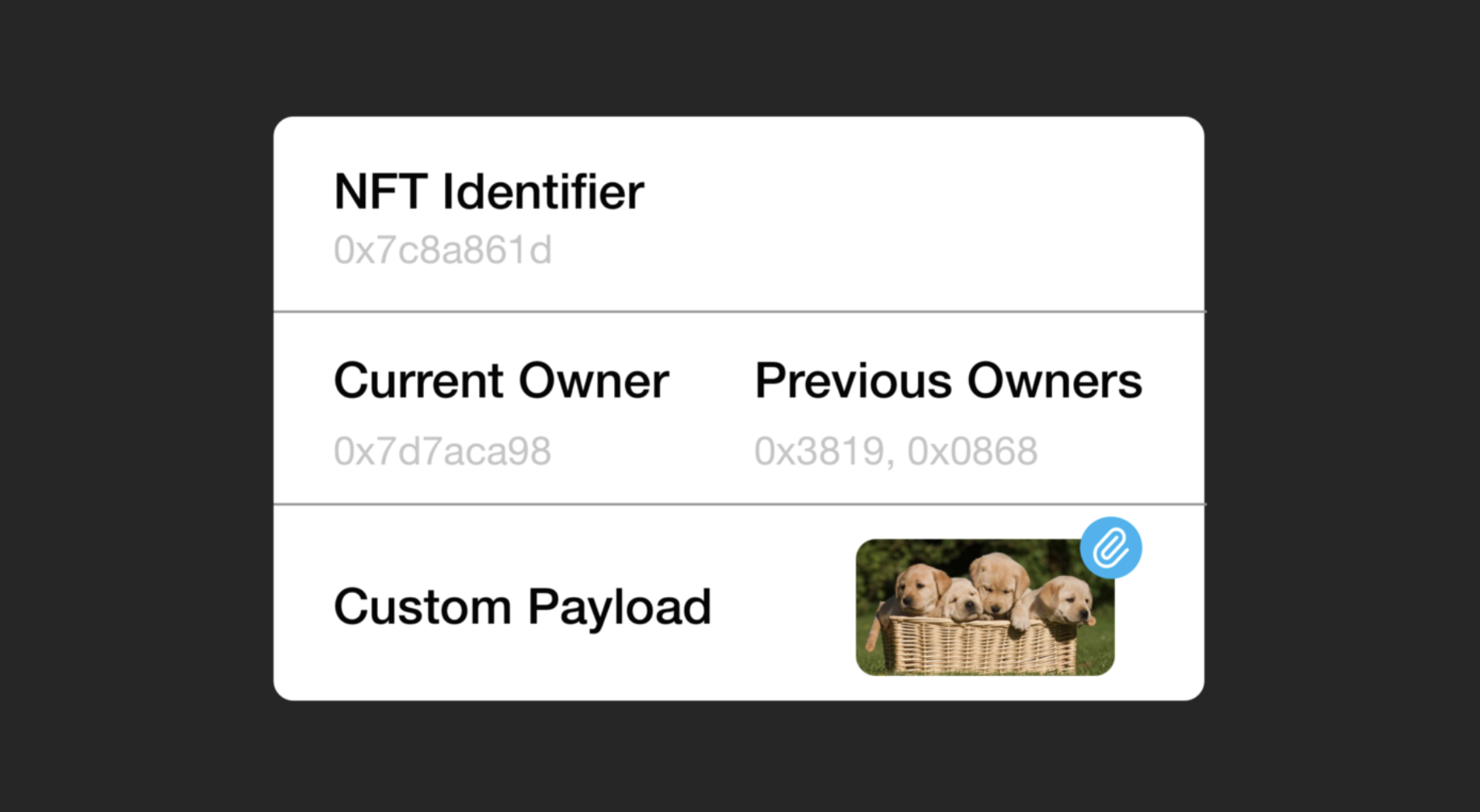

The anatomy of an NFT if we’re minting a puppy photograph.

At any point in time, NFTs contain four elements that define its state:

- A uniquely identifiable address. This allows everyone to refer to the same NFT over time. This identifier doesn’t change.

- A current owner. This is the wallet address that owns the NFT.

- All past owners. Anyone who has owned the token can be identified by looking back at the blockchain over time.

- A custom payload. In the case of Photography NFTs, this might be the actual photograph jpeg itself. For a short story, it might be a copy of the story text. In the case of other digital content, this might be a link to its presence online much like a hyperlink connects the web today.

Subjective Value Systems

My uncle’s a passionate book collector. He’s the guy who buys first editions in hardcover. He goes to the local bookstore to collect signatures when authors are on speaking tours. Over the course of forty years of collecting, this hobby has cost an immeasurable amount of time and money. And he would do it all over again in a heartbeat. I once asked him why he does it. He told me -

“Collecting brings me closer to the books and to the people who wrote them.”

Even though he does his collecting quietly, he is still a member of the larger collector culture. This community is scattered across the world with a colorful range of backgrounds and interests. Unlike the reputation that collectors are rich millionaires, most collectors look like my uncle. Middle-aged hobbyists with a passion for their niches. And diverse niches they are: art, books, cars, letters, trading cards, video game machines, and dolls. Just to name a few.

Despite the diversity of these interests, the guiding principles of collectors are largely the same.

Ownership history: The author or creator is how a work derives its original value. Who wrote the letter, who painted the portrait, who built the car. The lives of individuals are wrapped up in the work that they create. Owning the artifact itself connects collectors to these historical figures. Subsequent owners are also relevant to the item’s provenance. You want to prove that the work is legitimate and establish a trustworthy chain of custody between all previous buyers. This can further add to the work’s desirability: some collectors have fame in their own right, and an item previously owned by such a collector is more valuable than others.

Control: Like a deed to a house, buying a collectable becomes private property. You can choose to display it, modify it, or hide it away. You can drive it or keep it in your garage. In the case of art or other displayable collectables, this control becomes especially significant. It can double as a rare decoration or other showpiece that only you have access to.

Nostalgia: Depending on the artifact, the value might also be sentimental. It might bring you back to another time in your life. Trading baseball cards with your middle school best friend. Cruising down the Pacific Coast Highway as a teenager in a Datsun 280Z. Providing that nostalgia is worth paying for.

Scarcity: Like membership to an exclusive club, there is something very instinctual about acquiring scarce resources. For items that are typically collectables, there is a passionate community that wants the item — usually for the above reasons of ownership history, control, and nostalgia. This demand exceeds the supply; the constraint on supply further triggers that mammalian sense of scarcity. People either acquire the item or get left out of the community. There’s an in-group/out-group dynamic with owning one of a limited set of copies, which is magnified if you’re the sole owner. Scarcity is not the reason you collect a piece, but it increases the value of the pieces you already want.

Getting slightly less romantic, you can also view collectables as an investment strategy. As an asset class, art collection had one of the highest ROIs of the last decade with an 13.6% average appreciation versus a 8.9% average return of the S&P 500. For my uncle, this fact is less important than the others. But it’s more justifiable to spend money on a hobby when you have a sense that it’s going to maintain or increase its value in the long-term. The key here is that there needs to be a market that continues to value this artifact on the above four points. Ownership history, control, nostalgia, and scarcity underpin the long-term value of a collectable. Without these, there’s no demand in the market, and the value will eventually decrease to reach an equilibrium.

Unlike my uncle, I don’t own any collectables. I don’t collect signatures. I read extensively but my connection to the authors come from the words on the page and not the condition of the dust jacket. This showcases a difference in values. It’s probably a function of our two different childhoods and how the world has changed. Baseball trading cards were big in his circles in the 70s East Coast; the 2000s West Coast were focused on skateboards and gameboys. Even among two contemporary collectors, they’ll likely have different interests and therefore weigh the value of a single collectable very differently. The true value of a collectable doesn’t exist. The market value is inherently subjective and needs to be supported by a community with a large enough attachment to maintain the price. If the community shrinks over time, the value often goes down. If it explodes in popularity, values will rise accordingly.

What gives these things value?

A few weeks ago, Jack Dorsey sold his first tweet as a NFT for $2.9 million.

But what does that actually mean? His first tweet is hosted on Twitter, under his account, just as it always has been. It’s still there and will remain there as long as Twitter remains a solvent company. Unlike Sotheby’s auctioned artwork, if the NFT holder wants to remove it from public view and hang it in their private gallery, they can’t do so. That tweet is a digital artifact that’s hosted within Twitter’s ecosystem and is materially (both legally and technically) completely separated from the token that bears its same name. Instead, this NFT simply had a link to the original tweet. If you pull up the token’s address on the blockchain, you can see this link and the current owner of the token. We also know that Jack owned the original wallet that created the token.

So this token has a link to a tweet. Nothing more, nothing less. I can link to that same tweet and it’ll be worth nothing. So why is this NFT worth significantly more than the average house price in San Francisco? Well, one point is Jack did raise the money for charity. So a philanthropic bitcoin millionaire could justify the purchase on the basis of the eventual charity. In return they gain some press and notoriety. Hakan Estavi, now the proud owner of this original tweet token, owns a blockchain company called Bridge Oracle. If I had to guess, the free publicity certainly helped justify paying a heightened price-tag at auction. It was good for brand awareness.

But let’s assume this NFT is actually worth 2.9 million dollars. After all, there are cheaper ways to buy press and more straightforward methods to donate to charity. Most even have better tax benefits. How does it stack up against the axes of collectables?

Ownership history: Jack Dorsey is the one who auctioned off this tweet. Because of the publicity around the auction, it’s clear that Jack was behind this NFT, which gives real-world legitimacy to the token. Given the price range of the token, it’s also likely that there will be an interesting custody of owners over time. But the root value of the token comes from the fact that the co-founder of Twitter minted and sold it initially. His fame rubbed off on the NFT. Whether that matters to you, as the buyer, comes down to your impression of Jack Dorsey. Ownership history: check but somewhat relative.

Scarcity: Theoretically, Jack could issue another NFT that duplicates this same tweet. There’s likely enough publicity on this case and cultural pressure to stop this from happening. But some other actor could re-issue a token with the same link to the original tweet. So the custody chain comes into play here: there will only be one first token minted by Jack. This is the rare commodity. Scarcity: Check.

Control: By purchasing the token, you get no control over the tweet. You simply own a reference that cites the original. This is akin to a hyperlink on the regular web — just because you link doesn’t mean you have any control over the original content. Control: Negative.

Nostalgia: I was on twitter back when it was still twttr. While I don’t have a particular nostalgia for those days, it was a moment that heralded the social media age and everything that came along with it. Memes, influencers, presidential politics. There are inevitably other Twitter users who feel differently. But it’s hard to point to a group that has a nostalgia for this era that they would be interested in reliving — and would do so via tokenized ownership of this tweet. Nostalgia: Relative.

So call this 2.5/4. Not an insignificant number of boxes to check. But also not a clearcut victory for the underlying value of the NFT.

So that raises the last point: is this an investment for investment sake alone? Absolutely not. Let’s say you don’t care for Jack Dorsey and don’t feel nostalgia for Twitter. Parking money in an NFT is a bet that there’s a big enough market that feels differently, to one day bid up the price to higher than the $2.9 million. Unlike with established artists whose work can show valuation trends over time at auction, there’s no guarantee a market for this token will ever exist apart from the current novelty of NFTs and the charitable purpose of the original auction.

This is why I think about NFTs in the same way I think about other collectables. Most serious collectors would be satisfied with their purchase even if the fair market value went to zero. They purchased for the intrinsic, subjective reasons of ownership history, control, and nostalgia. The scarcity gives value to these other elements because the good is in limited quantity. But scarcity itself is not sufficient. Unless you intrinsically value the artifact on these levels, don’t park your money into NFTs as an investment.

Market Opportunity

Blockchains at their very basic level are distributed ledgers. They allow individuals to transact at any time without the need for an intermediary. There is valuable novelty here. I tried to sell a stock at 5:03pm last week only to be told that it will clear the next business day. I sold some Ethereum that same evening and it cleared instantly. Trading stocks within eastern business hours is an outdated constraint that is at odds with our age of globalization. I’m convinced blockchains and continuous trading are here to stay.

Are NFTs? We’ll see. But there are a few business opportunities that will be critical to ensure they have a fighting chance.

Human Identity

A critical piece of collector culture is ownership history. People care about the owners as human beings. Jack Dorsey, Picasso, Obama, etc. They don’t care about the anonymized wallet addresses that make up the blockchain.

Blockchains are anonymous by nature. Any user can have a wallet address; and this wallet is decoupled from any IP or personal identifiable information. Since the content of NFTs can be duplicated, the unique value are the past addresses that have owned this token. And ideally, these wallet addresses can be traced to real individuals that have owned the asset. Since human reputations give the legitimacy to the underlying token, this is critical in establishing a true chain of ownership and the scarcity of the good.

We need a trustworthy party that can link people to their authorized wallet addresses. So when there are rumors that Jack has issued a NFT, we can confirm the truth by looking at the source wallet and then connecting it back to Jack. Right now the alternative is publicity from news outlets or providing a mark of legitimacy on social media. These might be useful for famous creators. But for more indie creators without the name recognition, it needs improvement. Newspapers or past tweets are not the authoritative certifications of authority for a 2.9 million dollar investment.

A human identity system can have use-cases throughout the blockchain ecosystem. But none as clear as NFT histories of ownership.

Legal Ownership

We’ve only looked at NFTs that are simply links. However, there is a class of tokens that are backed by real-world assets. You might be familiar with an example of these as TUSD — tokens that are backed 100% by the US dollar and convertible to a real dollar at any time. This claim on the underlying US dollar is legally enforceable, facilitated through a real world contract that is forced to sell if requested by the blockchain token owner.

Now things start getting interesting. My friends over at the Stanford Blockchain Group are doing a lot of work to define the legal significance of a blockchain contract. They’ve already proved that you can construct a real-world entity (trust, charter, etc.) to take instructions from a blockchain contract. It couples a real-world contract that binds parties with a digital medium that defines the terms. The real-world contract is fixed and immutable. But it tells the trust executor to take all instructions from a dynamic source — the blockchain contract. If you control the underlying contract you effectively control the trust.

An NFT in principle could be minted in this legally enforceable fashion. You then own both the digital asset and the control of a physical good in the real world, which certainly would satisfy our condition of “control” that is so desirable in collections. As the owner of the NFT, you are free to trade full ownership over this underlying asset by digitally reassigning ownership of the token. Art industry intermediaries like Sotheby’s are cutout as middlemen because you can sell at any time on the open market. The tokens also have the built-in ownership history on the blockchain that an auction house typically provides as a certificate of authority.

I happen to find fractional ownership of these assets to be equally (or more interesting) than an NFT that owns the full thing outright. Instead of needing the millions to buy a full Picasso, you could own a fractional share of the artwork. This gives the whole asset an immediate liquidity premium by increasing the number of buyers that are able to purchase shares. There are a few players in this space who are doing the same on and off-blockchain. Masterworks seems to be one of the leaders in the space. I’m keeping a close eye on developments in this world.

Marketplace Design

To really build a seamless experience and expand the appeal of NFTs beyond those who already transact daily in crypto, marketplaces will need to make a few changes.

Legitimacy: NFT marketplaces need to place a heightened emphasis on building trust with end users through content curation and design. They need to make clear exactly what is being sold, who issued the object, and what legal terms the smart contract contains. Most of the current marketplaces are muddled with junk tokens and feature user interfaces that confuse instead of comfort users. Buyers need a sleek interface to securely trade cash into tokens.

Price: Depending on where you go, you’ll be looking at $70 to issue a token and $70 to accept any bid lower than 1ETH. Marketplaces need to allow initial listings to be created without a listing fee or with a minimal downpayment. Much like what Coinbase is doing with off-chain transfers if both parties are on Coinbase, and therefore saving from the blockchain transaction fees, this can easily be solved by the NFT auction brokers. Only create the Ethereum contract necessary to bring it into existence if there’s actually a buyer. Otherwise the auction will expire without the original creator needing to pay for a useless smart contract.

USD: Many collectors still naturally transact in USD, instead of Ethereum. Today, buyers have to exchange USD into ETH at an exchange, transfer it into a wallet on the NFT market, and then bid up the good. These are far too many steps, and each one can block or delay the next. It takes a few days to deposit USD funds, some time to transfer those funds between wallets, etc. Coupled with the fact that the auction might go for an unbounded amount of money — bidders might have to do multiple USD->ETH transfers as the prices keep rising. A more streamlined experience paying in USD is necessary to expand the scope of people who are interested in NFTs.

Closing

Don’t let the hype train of NFTs disguise from what they actually are. They’re a method to collect goods online, that may or may not be controllable by the NFT owner. If the underlying object has value to you and a similarly minded audience, they may even appreciate in value. But focus on the competitive strength of the offerings you’re looking at. Buy it because you want to be the proud owner of the element or the nostalgia; the market is far too early to give a strong signal on what the price equilibrium will look like over the long term. Otherwise, you might be buying the 21st century version of a pet rock.